By Terry Chao

Korean pop music fans have started taking lessons so they can understand the lyrics of their favorite songs.

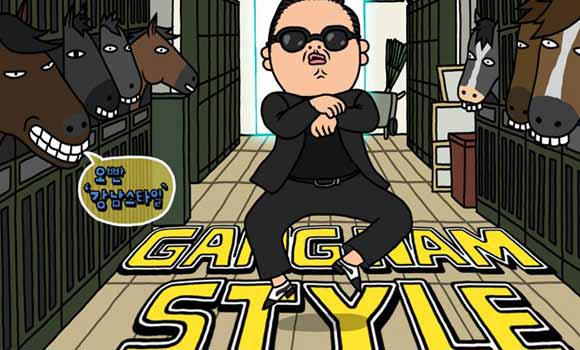

“Hallyu”: It’s a term that would have had Americans scratching their heads a mere four months ago. But thanks to a song called “Gangnam Style,” by K-pop artist Psy “Hallyu”—the term coined for the “Korean Wave” or the influx of South Korean entertainment and culture into other countries—is now as familiar as hip-hop in the States.

K-pop used to be a music genre largely exclusive to Asia. Now, with the aid of Internet streaming, fan sites and social media, K-pop fans have multiplied, crossing geographic and generational boundaries. K-pop fans run the gamut from 16-year-old high school students to 52-year old homemakers jiving to “Gee” from SNSD, a popular all-girl K-pop group, while doing the dishes.

“It’s kind of funny when I come home and see my mom singing along to SNSD,” says Lindsey Martinez, 18, who is also a fan of the group. “I feel a little embarrassed about it, but then again, it’s cool that she’s started liking the same kind of music as me. I guess it makes it a little easier when I ask her for concert ticket money.”

But these fans aren’t just your run-of-the-mill, poster-hanging, ticket-splurging groupies. K-pop fans like Martinez, who didn’t speak Korean before she started listening, have started taking lessons so they can understand their favorite singers’ lyrics.

“Sometimes it can get really frustrating when I really like a K-pop song, but I have no clue what they’re singing about,” Martinez says. “I mean, I can look up the translation later, but that can get really annoying. That’s definitely one of the reasons why I started learning Korean.”

At first glance, K-pop is like a sparkling, artificially-flavored exotic soda. It’s probably not very good for you and might not even taste very good, but it makes you thirsty for more once the glass is drained.

Eun Jun Lee, a private tutor teaching Korean, says business has been up since the release of “Gangnam Style.”

“I think it’s great that more people are becoming interested in Korean culture, be it because of a song or not,” Lee says. “Either way, I’m glad not just for the extra business, but also for the appreciation of a way of life that isn’t their own.”

Her roster of students went from four clients to 10 in a matter of weeks, which she attributes to her student’s increase of interest in not only K-pop, which has made them more interested in Korean culture in general.

“I have students that come to me and say that they want to be able to sing along to K-pop songs,” Lee says. “They’re just so willing to learn the language in order to do this, in order to be able to connect with what their favorite pop star is saying, or to be able to watch ‘Secret Garden’ without the subtitles. But I think that’s going to take them a little longer than they think.”

According to a study conducted by the Modern Language Association, enrollment of students taking Korean language courses in universities nationwide has risen by 19.1 percent between 2006 and 2009.

Additionally, the number of people who applied to take the TOPIK, or Test of Proficiency in Korean, has risen dramatically in recent years. In 2010, the number of applicants for the test, run by the National Institute for International Education, a Korean government organization had increased 65.8% since 1997.

Beatrice Chen, 20, admits she didn’t like K-pop’s bubbly, up-tempo sound when she first heard it. But the more she listened, the more she liked the infectious songs until she was inspired inspiring her to take up learning Korean as well.

“It’s very catchy, the songs get stuck in your head; you hear it once, you want to hear it again,” Chen says. “Like here it’s the ‘Call Me Maybe’ song, which is not even that great of a song, but it’s so catchy. And you want to hear it again.”

Yet Chen also questions whether the popularity of the song “Gangnam Style” would be negatively affected if its non-Korean speaking fans knew the actual meaning of the lyrics.

“People don’t understand what it actually means, which makes it even more funny,” Chen says. “I actually know in translation what it means. And if people really [understood it, they might think] ‘This song is actually really stupid.’”

Samantha Sanchez, 16, started learning Korean after becoming a fan of Super Junior, a 13-member K-pop boy band. But she says the language barrier doesn’t change the way the music makes her feel.

“Listening to their music makes me happy,” Sanchez says. “Even though I may not understand what they are singing, it doesn’t matter. Music is music.”